beauty box kenya (2014)

In early 2014 I was approached by a friend to work for his father’s safari tour business teaching his new cook to prepare food that his predominantly European clientele would eat. The deal was for two weeks of my tuition, I would get two weeks all expenses paid of the full Kenyan, Maasai Mara experience. Although this sounded intriguing, I was in the first year of my masters degree, and simply announcing to my supervisor that I was taking a month off to go on an African safari probably wouldn’t have gone over so well… Answer: tangential research.

My previous research and collection of work had considered the notion of how we view our own reflection in the context of western canons and contemporary beauty, and this seemed like an obvious opportunity to test the possible/probable similitudes of this experience. The challenge would be in the translation away from reliance on cultural notions of beauty, and toward universals, or common understandings of beauty.

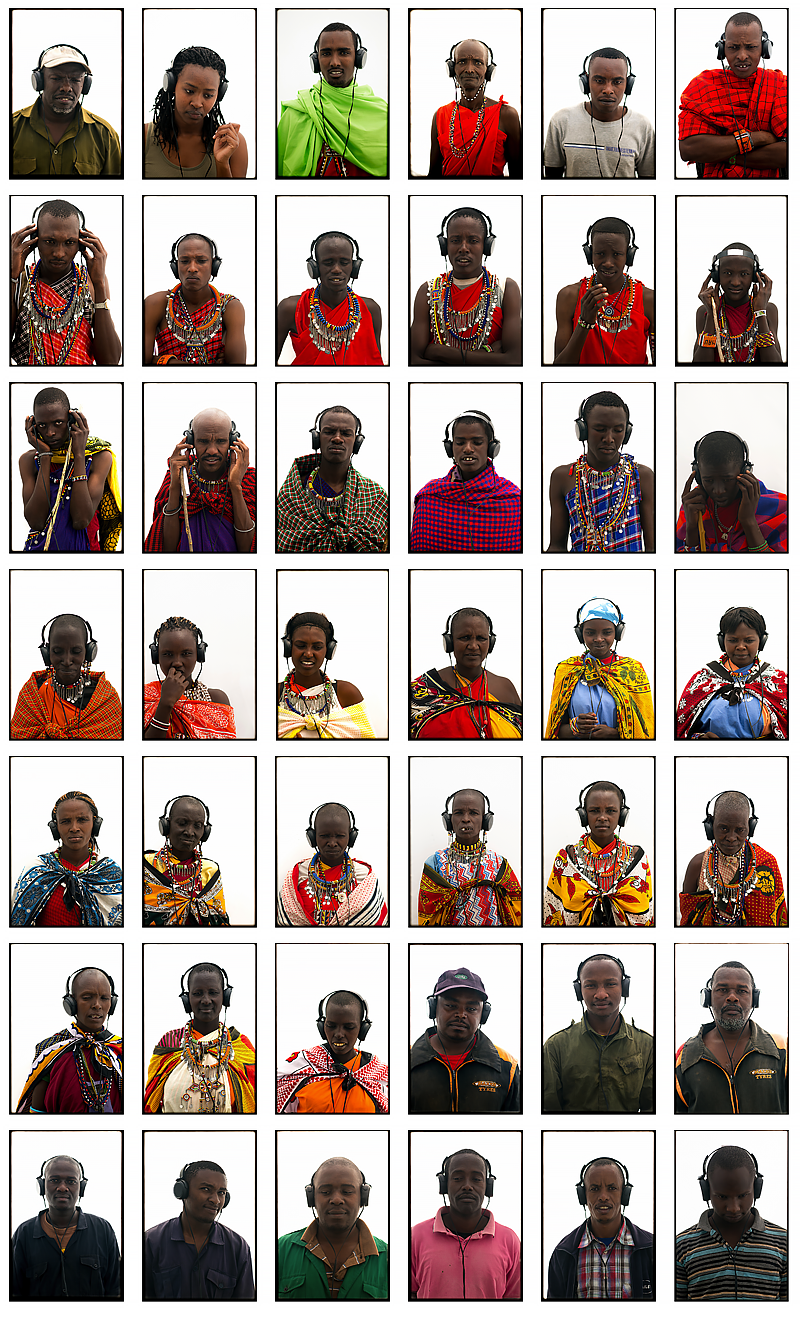

You can see from other posts here on the website the experiential artwork beauty box, which is a large, heavy device from my collection Eyes of the Beholder. A participant chooses to engage with it after reading an introduction, and then pushing an activation button. This then turns on lights and sets into motion an audio recording as well as an autonomous camera which captures images of the participant every 5 seconds for a minute. It is a complicated device. In order to repeat a similar experience in Kenya I was going to need to make a significantly low-tech version, which you can see made here from aluminium tube, some plastic tarp’, some sail cloth, a two-way mirror, rope, and hung off the side of a land rover. I had the help of some fantastically helpful and resourceful guys at the camp who could fashion something out of nothing, and together we made it happen. You can see them at the end of the portrait series.

Speaking of the portraits… to me, this artwork is experiential, in other words: it happens inside the curtained booth, experienced by the participant, there and then. These pictures are documentation of the artwork. There is of course, a contradiction, in that these images, although not taken by a photographer, have been edited, and then this series curated, so there is a creative hand to that which you view, and as such can and probably should be called portraits, but, my original intent with all the beauty box artworks, was the experiential.

And so to the participants… this was qualitative research, not quantitive – no answers were required to any questions asked. No specific demographics or age groups were sought. I was happy for anyone who was interested in taking part to participate, and as such you can see that the order of images is the order of participation… the kitchen manager (who helped me invaluably throughout my stay); the safari tour manager (my dialect translator/recorder); the camp warriors (who protected us at night from the beasts – a father and son team); a driver; the maasai mara chief; the maasai mara men; the maasai mara women; the mechanics from the garage and various workers from around the camp.

see the full size images here

what is beauty?

is it in the shape of a face, or body?

or, does it come from inside of a person?

is beauty the smell of a baby’s head?

is it the memory of your mother’s hand on your head in the sunlight?

is a sunset or sunrise beautiful?

is there beauty in art?

do you see or feel beauty?

do you think african beauty is different to western beauty?

do you think beauty changes as you get older?

do you think about beauty?

does beauty give you pleasure?

is beauty more often in nature, or man made?

do you own things of beauty, or are they for everyone to enjoy?

when you think about it, what is beauty to you?

these questions were asked over a one minute period, one photo was taken every 5 seconds during this period to document the visual response to the face staring back at the participant.

nb: as this project was part of a Master of Fine Art research degree, appropriate explanation of creative and academic intent was explained to all concerned, and then required consent was sought and granted by each participant.